By Susan

This blog post is late.

This blog post is late.

There are many reasons for this, including dissertations, meetings, supervisions, job searches, job postings with incorrectly listed due dates (surprise!), the works. But it hasn’t been all work and hardship on my end. Or at least, it hasn’t been all hardship. Because, in the past few weeks, there’s also been this:

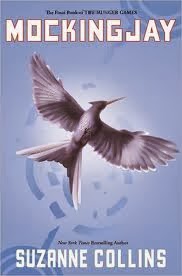

And, to come on Thursday, this:

Welcome to the world of an academic: specifically, one who studies contemporary YA dystopian literature.

Of course, it's not all fun and games. There's a pervasive attitude that work on children's texts can't really be 'work' (I tend to encounter this when I tell people what I do at cocktail parties. This bit comes right before they ask if I plan to be a kindergarten teacher, and slightly after the 'that must be easy: your books are so short!' Please see Allegiant for clarification on this particular matter....all 544 pages).

|

| Welcome to my life. |

The slightly (or not so slightly) dismissive overtones of these comments aside, the underlying idea tends to be this: if it's fun, it can't possibly count as 'work'.

There are several responses to this attitude, which I'd like to offer here. First, let's query the assumption that work ≠ fun. This seems a sad attitude to me. Why not enjoy what you do? Or, perhaps more importantly, when work is hard and everything is happening all at once, and you're fighting to stay on top, and dealing with the boring bits that you've been putting off (because let's be honest, we all do it), what's wrong with being able to stand back for a moment and say: "well, at least I love it"?

Which leads me to the second assumption, the one which gets me even more, and strikes me as particularly insidious.

|

| Exhibit A: 'Fun' is relative |

And it is this: that children's literature scholars only study that which is 'fun'.

This is patently untrue.

|

| Lies! |

Children's literature scholars study texts which are important. We study works which are interesting, or unexpected. We study books which are powerful and problematic in turn, revered and rage-inducing. And yes, we are oftentimes deeply drawn to the books we study. Shouldn't that be a pretty standard prerequisite for passion?

Some of us look to lesser known texts, some - like me - to the highly popular. Uniting us all is a deeply rooted belief that these texts, the narratives they perpetuate, and the shifts they mark in attitudes towards young people, matter. Beneath our 'love' for any one particular text is an acknowledgment that texts for children can often possess deeply troubling, complex cross-currents of adult ideology. Beneath our 'hatred' of any number of texts is an acknowledgment that many of the most problematic of children's books draw huge readership - speaking to child and YA audiences that cannot simply be dismissed or explained away as 'immaturity'.

|

| Spoiler Alert: Girls who wear lipstick don't get to heaven |

|

| Sometimes, Peter Pan kills people. Specifically, other children. |

So, to conclude, the life of a children's literature scholar can be hectic. It can also, alongside that, be fun. But just as 'children's' does not connote 'simple', fun does not connote 'easy', or lacking in value. And 'fun' is nowhere near the prerequisite for the study of a children's text. To assume so is to do a disservice to the academics who study children's literature, but more importantly, the authors who produce it, and the audiences who consume it.

Though, let's not lie: there's something to be said for some fun. And I'm really, really excited for Catching Fire....